Holes of Unknown Origin Found in Tyrannosaurus rex’s Jawbone

A new analysis of enigmatic pathologies in the lower jaw of Sue the T. rex — one of the largest, most extensive, and best preserved Tyrannosaurus rex specimens ever found — reveals all the characteristics of wound healing in the absence of infection.

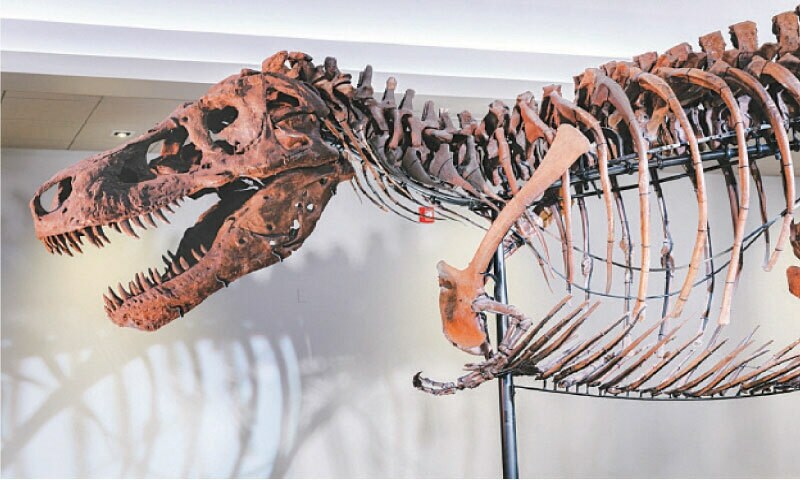

Dr. O’Connor with the skull of Sue the T. rex at the Field Museum. Image credit: Katharine Uhrich, Field Museum.

“These holes in Sue’s jaw have been a mystery for decades. Nobody knows how they formed, and there have been lots of guesses,” said Dr. Jingmai O’Connor, a paleontologist at the Field Museum of Natural History.

One early hypothesis was that Sue suffered from a fungus-like bacterial infection, but that was later shown to be unlikely. It was re-hypothesized that this individual had a protozoan infection.

Protozoans are microbes with more complex cell structures than bacteria. There are lots of protozoan-caused maladies out there; one common such disease is called trichomoniasis, caused by a microbe called Trichomonas vaginalis. Humans can get infected with trichomoniasis, but other animals can catch it too.

“Trichomoniasis is found in birds, and there’s a falcon specimen with damage to its jaw, so some paleontologists thought that a Trichomonas-like protozoan might have caused similar damage to Sue,” Dr. O’Connor said.

“So for this study, we wanted to compare the damage in Sue’s jaw with Trichomonas damage in other animals to see if the hypothesis fit.”

In their study, Dr. O’Connor and her colleagues took high-resolution photos of the holes in Sue’s jaw and analyzed them for signs of bone regrowth.

They then compared the holes to healed breaks in other fossil skeletons.

They also examined the healed bones around trepanation holes made in skulls by Inca surgeons and healers in ancient Peru.

“We found that Sue’s injuries were consistent with these other examples of bone injury and healing. There are similar little spurs of bone reforming,” Dr. O’Connor said.

“Whatever caused these holes didn’t kill Sue, and the animal survived long enough for the bones to begin repairing themselves.”

The holes in the jaw of Sue the T. rex. Image credit: Rothschild et al., doi: 10.1016/j.cretres.2022.105353.

The authors also examined a bird skeleton with history of trichomoniasis.

“You do see signs of infection, and they are in the back of the throat, but there aren’t holes bored through the jaw like we see in Sue. Trichomonas, or a similar protozoan, doesn’t seem to fit,” Dr. O’Connor said.

“So what did cause these holes, if not an infection? We think they’re bite or more likely claw marks, but I don’t think that makes sense.”

“The holes are only found in the back of the jaw. So if they are bite marks, why are there not also holes at the front of the jaw? And you don’t see rows of holes, or indentations, like you’d see from a row of teeth, even a row where the teeth are different heights. They’re just random, all over the place.”

The team’s hypothesis suggests that the claw marks are the result of courtship behavior.

“But if bite or claw marks are off the table, there are lots of possibilities remaining to explain the holes — some of which we maybe haven’t thought of yet. But she’s keen to help figure it out,” Dr. O’Connor said.

“The more I started learning about these jaw holes, the more I was like, ‘This is really weird.’ What I love about paleontology is trying to solve mysteries, so my interest is definitely piqued.”